It’s on the news: we’ve a new DeepSeek moment. A bit less fancy, maybe, but quite a breakthrough that may redefine LLMs. In it’s most recent paper, the whale presents DeepSeek-OCR, a powerful new OCR (Optical Character Recognition) model.

While its OCR capabilities are impressive, the real intrigue for us lies in a more fundamental question it prompts.

As a community, we’ve defaulted to text tokens as the universal input for LLMs. But what if this is a wasteful, limiting bottleneck? What if pixels are a more effective and natural input stream?

The Case for a Pixel-Only LLM Diet

Imagine an LLM that only ever consumes images. Even pure text would be rendered into an image before being processed. This might sound counterintuitive, but the potential benefits are compelling:

1. Superior Information Compression

The DeepSeek-OCR paper hints at this: visual information can be more densely packed. A single image can convey the semantic meaning of a paragraph of text, along with its visual presentation. This could lead to significantly shorter effective context windows, translating directly into higher speed and lower computational cost.

2. A Radically More General Input Stream

Text tokens are a narrow, impoverished data type. By switching to pixels, your model’s “language” becomes the universal language of visual information. The input can be:

- Formatted Text: Bold, italics, colors, and font sizes—all of which carry meaning—are naturally understood.

- Mixed Modalities: Charts, diagrams, memes, and real-world photographs are processed natively alongside text. No more complex, multi-modal pipelines; everything is just an image.

3. The Power of Bidirectional Attention by Default

Text generation is autoregressive—we predict the next token from the left to right. But understanding text is not. When you process an image, there’s no inherent sequential order. The model can use bidirectional attention across the entire “scene” from the start, leading to a richer and more powerful understanding of the input context.

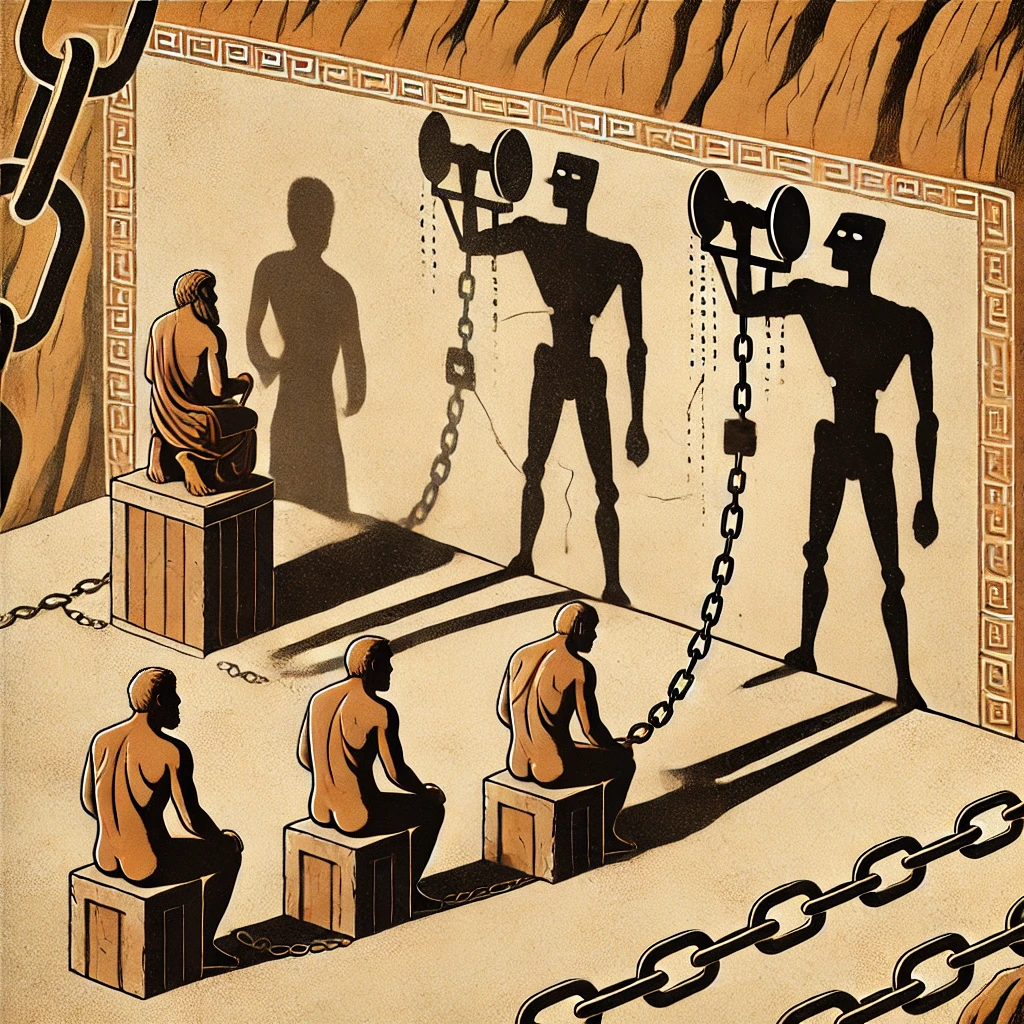

The Tokenizer Must Go

This is a hill we’re prepared to defend: the tokenizer is a problematic relic.

It’s an ugly, separate preprocessing stage that breaks end-to-end learning. It imports all the historical baggage of Unicode, byte encodings, and security vulnerabilities (continuation byte attacks, anyone?). Most damningly, it severs the model from the real world.

Two characters that look identical to the human eye can be mapped to two completely different, unrelated tokens. A smiling emoji becomes a weird, abstract token, not a visual representation of a smile that can benefit from the model’s inherent understanding of faces and emotions.

The tokenizer creates a brittle, artificial layer between the user and the model. Replacing it with a direct pixel-based interface would be a monumental step towards more robust and intuitive AI.

The Practical Path Forward

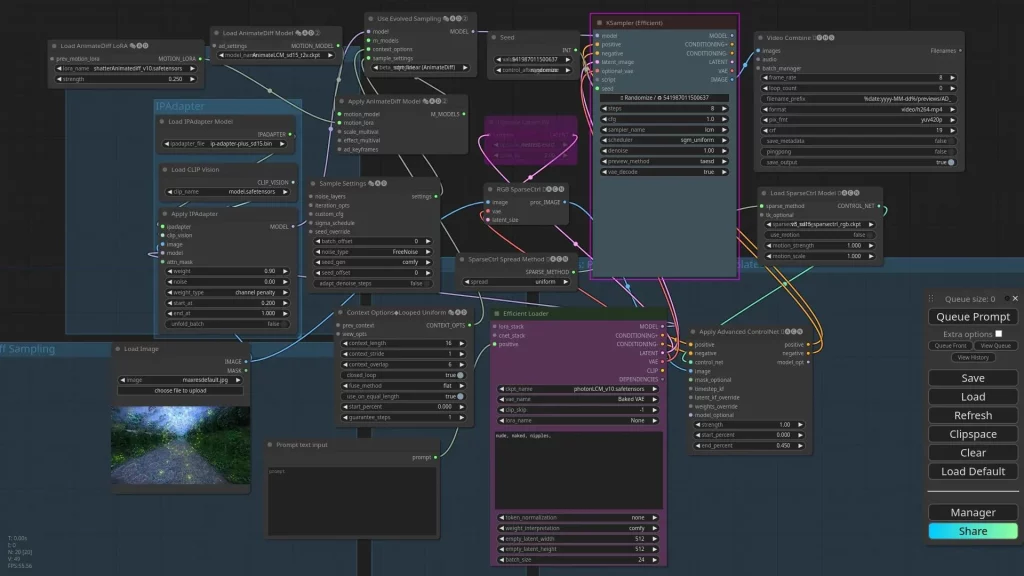

So, what would this look like in practice? The most viable architecture today is a Visual Encoder + LLM Decoder.

The user’s message—whether it’s a screenshot of a document, a photo of a whiteboard, or a rendered snippet of text—is fed in as pixels. The visual encoder processes this into a latent representation that the LLM decoder then uses to generate a coherent text response.

This approach elegantly sidesteps the most significant technical hurdle: generating high-fidelity, coherent images as output. For the vast majority of practical applications, we want a textual assistant, not a paintbrush. We keep the powerful text decoder we’ve spent years perfecting and simply give it a better set of eyes.

Conclusion: A Vision-Centric Future for LLMs?

OCR is just one application in a much broader paradigm. By framing all inputs as visual tasks, we unlock a world of generality and efficiency. While the text-only tokenizer has brought us far, it may be holding us back from the next leap in AI capability.

The question isn’t just whether visual tokens are more effective for some language tasks—it’s whether they are the universally better foundation for building general-purpose, multimodal reasoning systems.

The future of LLM inputs might not be text at all—it might be a stream of pixels.